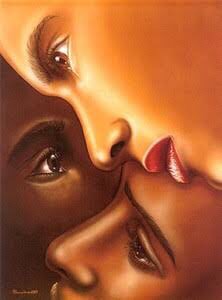

Colourism: “Prejudice or discrimination against individuals with a dark skin tone, typically among people of the same ethnic or racial group.” (Oxford Dictionaries)

Usain Bolt told Ian Boyne in an interview on Boyne’s television programme, Profile, of his experience with classism and racism in Jamaica (See Gleaner article based on the interview). I reckon that one of those instances was an incident last year where the wife of a popular dancehall artiste and Bolt’s neighbour blasted Bolt on social media about the noise, including music, possibly her husband’s music, coming from his apartment, which she said was causing her and other neighbours annoyance.

That was fair since consideration must be made for one’s neighbours in a residential neighbourhood when hosting parties and other gatherings. What was appalling, however, was her suggesting in her rant that he should ‘go back where he came from’ because, by her reasoning, he is not fit for the upscale community.

Bolt’s revelation of such classism in the interview came as a total shock to many Jamaicans. No, not really. Racism, on the other hand, is a bit difficult to comment on as racism is not the term typically used when discrimination is by a member of one’s own racial group. The better term would be colourism. Classism and colourism form a part of the fabric of Jamaican society, however, I’ll focus on the latter.

I remember the first time I became ‘colour’ aware. I was about seven years old and another child and I were having a random conversation as children are prone to do, when she said “A bay mek mi browner dan yu”. That can be loosely translated to boasting that her skin tone was lighter than mine. I retorted “No!” to which she put her foot next to mine to show me the difference between our hues.

Prior to that I had never thought of myself as anything as it relates to colour because I hadn’t been confronted with anything colour-related. From then on, however, I started becoming more and more self-conscious and aware of conversations and words regarding colour.

Nuttn too black nuh good

In Jamaica, a dark-skinned individual with no evident features of being ‘mixed’ is referred to as black. Telling someone ‘yu black like…’, translated as you have very dark skin, is an insult. Other negative expressions associated with being black include black and ugly, black gyal (black girl), dark like midnight, nuttn too black nuh good (anything that’s too dark or black is not good), tar baby, dutty nayga (dirty *clears throat* negro), black monkey and so on. However, there is the quasi-compliment of being called black and pretty or black and cool – the ‘positive’ expressions associated with being black.

Because being black is not synonymous with being beautiful, hence, beauty must be qualified in the rare instance in which a black person is deemed beautiful. The first time I heard a positive expression regarding my black skin that didn’t attach the qualifier ‘and’ or ‘but’ was as an adolescent and it came from persons from the Rastafarian community, who usually refer to black women with terms such as black empress, African queen and the like.

A light-skinned individual, hinting at one being mixed with either white, Asian or light Indian ancestry for instance, is called brown – the origin of the term ‘browning’. Browning is usually used to refer to a light-skinned female and can be expressed as a compliment to said female. Being ascribed this title is synonymous with or perceived to be having status, and being liked, loved or desired. Historically speaking, the browning has been placed in a hierarchy above blacks.

Now let me hasten to add that I am aware that colourism is not unique to Jamaica, nor to black people for that matter. In many Asian cultures, for instance, individuals with lighter skin tones are considered more beautiful than those with darker hues. Hence, the high incidences of skin bleaching in those cultures. However, my focus here is Jamaica as I have an intimate knowledge of the socio-cultural contexts of colour in Jamaica, greater than that of any other country.

Love me browning

Many moons ago, before emphasis on merit became the sole requirement in job application and hiring processes, the browning was the standard, particularly in banking institutions and reception areas of companies and other establishments where an employee makes frequent contact with the public. A black individual had very little chance of landing such a position.

Sadly, still, this practice has not disappeared completely (see Gleaner article). The browning has been the subject of several children’s games such as ‘brown girl in the ring’, and songs such as Buju Banton’s Love me Browning, a song that received so much backlash that the singer subsequently recorded Love Black Woman to appease the masses. The browning has therefore been an ideal to which many women have aspired, evident in the practice of skin bleaching among many Jamaican women, and more recently, men, such as popular dancehall artiste Vybz Kartel.

Many cite beauty, becoming more appealing to the opposite sex, upward social mobility and trend as reasons for them bleaching. This begs the question of where the people of Jamaica, a country of predominantly black people, got their standard of beauty and perception that light skin equates to beauty. How do we move past this standard of beauty, which leaves many who don’t fit into this standard with feelings of inadequacy, low self esteem and lack of confidence?

The role of slavery and colonialism

A former colony of the U.K., Jamaica has been strongly influenced by European culture. Now, I’m willing to wager that the predominantly West Africans who were made slaves, on arrival to their new home in Jamaica, didn’t suddenly realise that a light complexion was the ideal. It would have taken years and years of social and cultural conditioning to reach to such a perception.

I would also wager that the preferential treatment given to the light-skinned offsprings of slaves impregnated by slavemasters had something to do with that conditioning, and has been at the root of colourism. Being given some prestige by slavemasters, light-skinned individuals were more trusted and hence seen as trustworthy.

The perception was the opposite for dark-skinned individuals who were considered ‘lazy’ and ‘dishonest’. Oh the irony – that a stolen people who were forced to work and help build the British empire to what it still is today would be labeled as such. Still, light-skinned blacks bought into the notion, no doubt because of the privilege their status afforded them.

There’s the common argument of ‘get over it’ and ‘move on’, as we’re no longer enslaved nor colonised. Yet, one does not simply wipe the slate clean of four hundred years of conditioning, which systematically painted a group of people in a negative light, so that that group now magically views themselves positively.

Furthermore, the society we live in still operates under rules that continue to reinforce some of those negative stereotypes regarding colour. Therefore, putting the cart before the horse will achieve nothing. In other words, we can’t attempt to alter perceptions and beliefs about colour without first addressing the stereotypes and systems which serve to perpetuate discrimination based on colour.

As we think on the struggles endured by our ancestors and the price they paid for the freedoms we enjoy, we must also examine the residual effects of slavery, one of which is colourism, and the hindrances it poses to our relations with each other.

—

Written by L.M. McBean

I am doing a research on classism and colourism and I across this article. It is well researched and is an eye opener. Excellent article!!

LikeLike

Unfortunately colourism is,alive and well in Jamaica…we pull the,wool over our eyes if we say it does not exist. So loving the skin you are in and being confident in who you are is definitely critical in this current landscape and knowing tgat we are #enough

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article.

We need to love the skin we are in. History has dictated otherwise and I oftentimes wonder if the damage can ever be undone.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed. I’m using this article as a secondary source for my IA. Light must be shun in schools regarding this sensitive topic as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting article.

LikeLike

Very nice. I look forward to reading all your posts!

LikeLike

Thanks for the support 🙂

LikeLike